The Ownership Paradox

Hundreds of years ago, being wealthy meant owning physical assets—such as gold, land, and heavy machinery, to name a few. It is estimated that Mansa Musa I, the 14th-century emperor of Mali, was worth approximately $400–$500 billion in modern currency. Most of this was gold; in other words, physical assets.

Around the 18th century, England experienced the Enclosure Movement. Before the Enclosure, peasants had usufruct rights to the land, meaning they had the right to exploit the land but didn't necessarily "own" it. There was a common right to the land. That changed after the Enclosure. It allowed for the privatization of land through fencing, and as a consequence, the wealthy ended up owning more while the less privileged fell into deeper poverty—partly due to a lack of affordability, the loss of customary rights, or because they received only tiny portions of land. Whether the Enclosure was appropriate is beyond the scope of this essay. The point here is that land and physical assets were used as a measure of wealth, and rightly so, because at that time, they allowed people to accumulate wealth.

Even today, wealth is measured by what you own, and perhaps even now, it is still linked to physical assets to some extent. What I am saying here is that wealth, materially speaking, was measured by weight or physical rights.

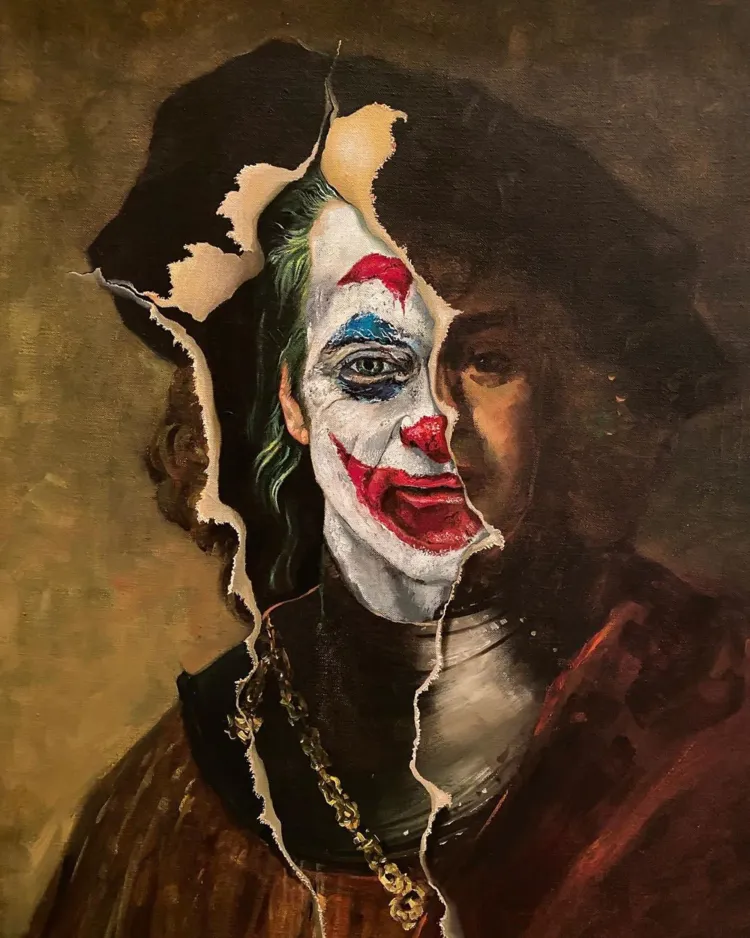

Paradoxically, the wealthiest among us in the 21st century are often "weightless."

When you think of wealthy people nowadays, you are most likely not thinking about the amount of land they own. In fact, it is more probable that you think of someone who owns businesses or shares in businesses rather than a peasant farmer. We used to define people's wealth by what they intrinsically owned, mostly physically, but this definition falters in modern times.

If your wealth is defined by your physical ownership of assets, then who are you when you own a Netflix subscription? You might say, "But I bought the TV I use to watch Netflix." Yes, you own the physical asset ,the TV ,but of what use is the TV if you can't use it without Netflix, YouTube, or whatever external service you run on it?

In the past, the wealthy owned the land, and the peasants worked it. Today, the wealthy own the Platforms Netflix, Spotify, AWS and we simply rent access to them. We have moved from paying rent for a cottage to paying rent for our culture.

The real 'weightless' wealth isn't the subscription itself; it is the ownership of the digital infrastructure.

In fact, the hierarchy of value has flipped. Today, I could rent a plot of physical land from you to build a server farm. Even though you own the soil, the 'weightless' code running inside my servers might generate more financial reward than your land ever could. Eventually, the tenant becomes rich enough to buy the landlord out. The physical now serves the digital.

One could easily argue that we have entered an enclosure in our own 21st-century version: the Digital Enclosure. We essentially moved from open access—in this case, free TV content access (obviously, we were being sold on ads)—to platform silos. We have the right to stream, but the fences and lands are owned by others.

In fact, I can go as far as to say you cannot bequeath a Spotify or Netflix subscription to your children. Well, you can, but they will have to pay to keep it, in which case they are better off creating their own subscriptions.

I might sound anti-modern regarding ownership, but I am actually not; if anything, I am pro-ownership. We have built several digital products and will build many more to come. However, the servers on which those products are hosted do not belong to us. We are merely renting them. The argument could be: "Why don't you simply buy your own physical server and host whatever you want on it?" I can. But that would easily become more of a liability than an asset. Keeping it running 24/7, cooling it, dealing with power outages, electricity bills, and so on—the list goes on. If that alone does not deter one from pursuing this project, then what will?

However, ownership has changed. It is no longer what it used to be, and we need to understand how to make it work for us. I am not claiming I have all the answers, because I don't. I am merely asking the question: What does the future of ownership look like, and what have we learned from the past few years? It is definitely not owning more land.

If it's not land, is it Control? Is it Intellectual Property? Is it Attention?